When it comes to formal dinner parties, there are three types of service that you will hear about:

Service a la Francaise or French Service (sometimes called English Service in America)

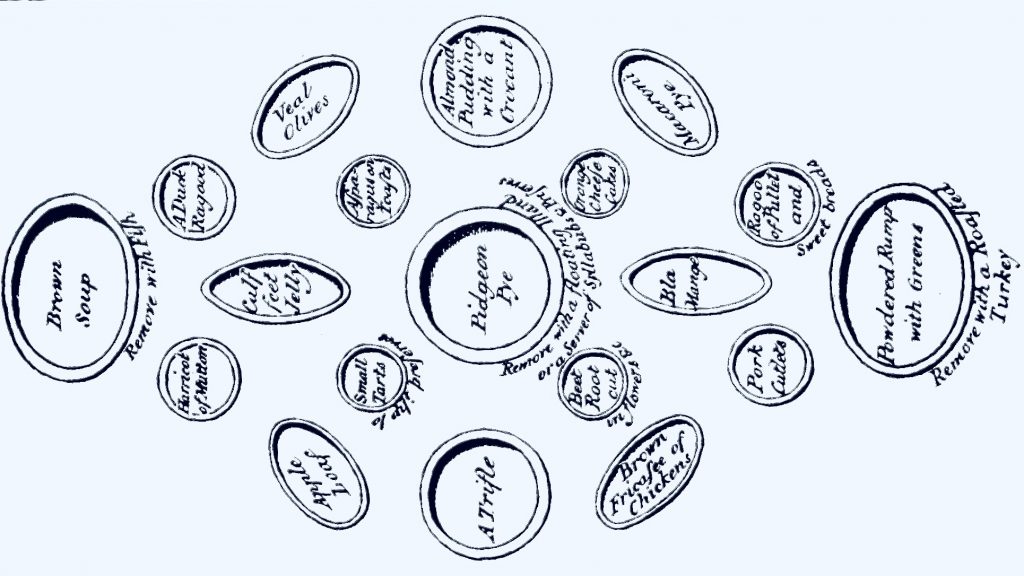

What preceded the type of service you see on shows like Downton Abbey? Before the Victorian era, tables were laden with food that was served in two or three courses. Sweets and savory both appeared on the table at the same time. This isn’t to say that servants weren’t used, they were. Footmen would bring new platters and tureens in, others would remove platters. This is why certain dishes were, (and still sometimes are) called removes. Servants also refilled glasses and replenished ewers for water and decanters of wine.

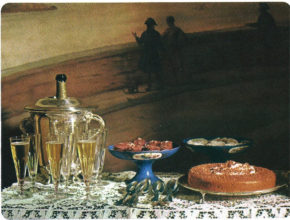

Whole joints of meat would appear on the table, pies filled with meat and towering jellies. Ice cream in cooling buckets with ice below and above were placed next to entrees.

A great example of how this might have worked is in the documentary, Having A Ball, where Ivan Day recreates the type of meal that would have been eaten at the Netherfield Ball in Pride and Prejudice.

Service a la Francaise would have been much more informal than we think of now. We mostly seem to picture the myriad of Edwardian rules when we think of the upper classes, (or middle classes for that matter) eating a formal meal, but Francaise was hallmarked by guests helping themselves and each other. Reaching for dishes was permitted and guests were able to eat only what they liked on the table and in the order they wished, rather than having to each whatever was prepared in a pre-ordained order.

Fun note: It is said you could tell if a host or hostess didn’t like someone if they placed the nicest dishes out of reach. This was sometimes so pointed as to set a guest’s favorite food at the end of a long table where they were unlikely ever to get a taste.

After the Regency era, when a la Francaise service was used by the middle and upper middle classes where numerous footmen were not available, the soup was served from a tureen by the host. As these were dinners and not banquets, the host then carved the meat. Everything else was up to the guest until the end of the meal when the hostess took over. She would serve the coffee, salad course and the dessert. This still meant that there was a cook and waitress, butler or general housekeeper to make the dishes and place them on the table.

It’s important to note that carving the meat was an activity of great importance for men. Being able to carve well was considered one of the gentlemanly arts. Partly this was down to the fact that men hunted a great deal and shooting parties were a large part of a gentleman’s social calendar. Each type of meat, each joint or cut of meat, had it’s own practice for carving. To carve badly was a real embarrassment. Also, the practice of the host carving allowed the host to express his largess by giving the choicest cuts of meat the the most valued people at the table. As well as showing kindnesses like remembering how a guest liked his meat served and to generally show himself off as the well-bred leader of his household.

As time pressed on, French service was adapted for the type of dinner parties that most of us give today. Everything is placed on the table and guests tend to help themselves. No servants are needed since we rarely have more than three courses. Up until very recently, dessert and the makings for coffee would have been on a side board or brought into the living room on a cart so that she hostess could serve the guests. Now we just tend to clear the table and put the dessert down ourselves.

Service a la Russe or Russian Service

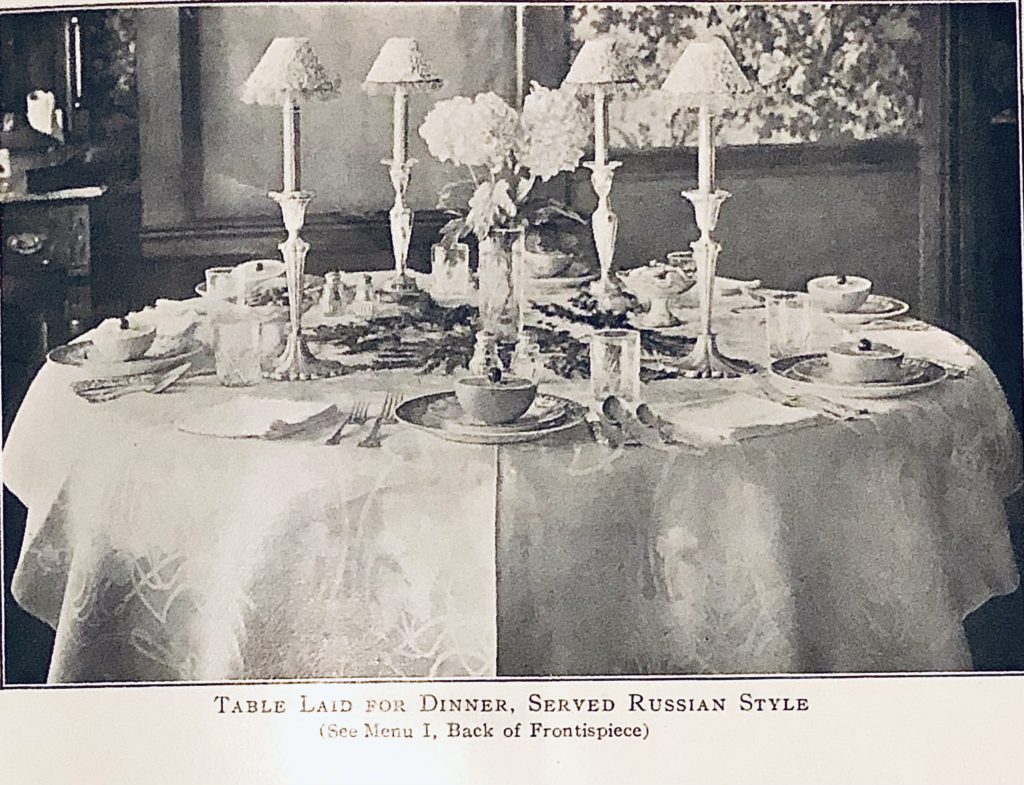

Russian service comes from an idealized version of the service seen in Russia in the early 19th century. While Russia at the time may have been backwards in some respects, what it had in spades was poor workers and serfs. Even moderate households could have an astonishing number of servants. This allowed for every dish to be made, plated and served to each guest individually. Europe, not be be out done on the grandiosity scale, followed suit. Russian service was introduced to France in 1810 and quickly gained favor.

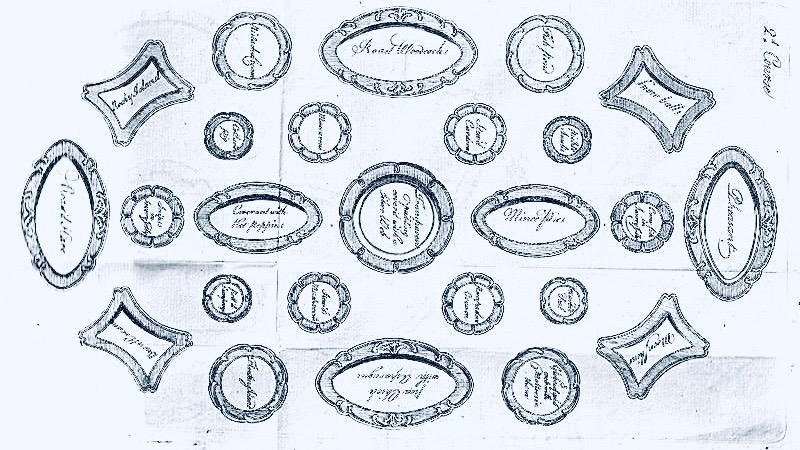

All the food is prepared and plattered in the kitchen and then brought to the table by help. The most important difference between these two services is that carving is done away from the table. Each portion was to be made equally so that every plate would look exactly the same. Footmen would bring a platter or dish to each guest and each guest would take a portion for themself or the course would come plated attractively. When you didn’t want a serving, you were able to refuse.

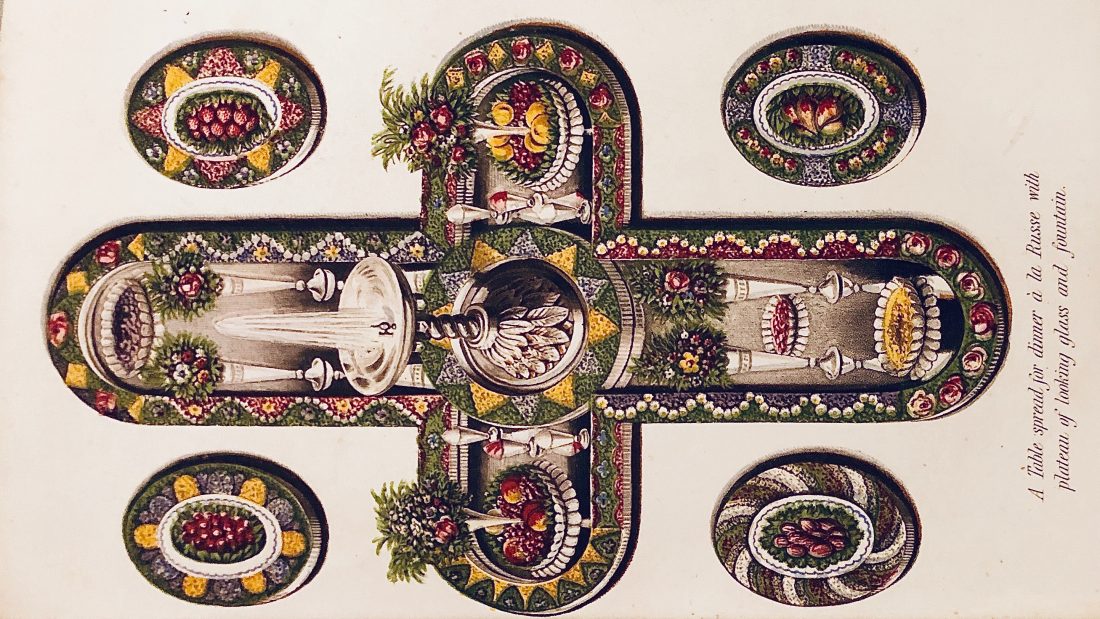

Service a la Russe, began being used in England as early as 1829, but it would not have looked like what a late Victorian or Edwardian would have known. There was a transition period where courses still numbered two or three with multiple dishes on the table. Dessert was on the table when you arrived, forming lines down the table. The Center might have a centerpiece of flowers or fruit or a sugar sculpture.

In the middle victorian period, sweets and savories began to be separated, with the third course becoming only desserts. A lovely cake or dessert might be shown to the guests, but then sliced in the kitchen, in the fashion you see at weddings. Buckets of ice cream were replaced by small molded ice creams on individual plates. Again, this is just a general rule, many cookbooks maintained that everything should be on the table to allow guests to eat the way they wished.

As England became wealthier and it’s rich, richer – the number of servants in a wealthy household increased. Ideally, every guest had a footman, though formal service could be done with less waitstaff. In Edwardian times, this would have been your footmen serving the dishes and the butler pouring the wine.

Now I don’t mean to imply that this was some sort of difinitive happening, new customs take time to be adopted, faster in the cities and among those who already had large staffs of servants, slower as you fanned out across a country. In the same way that old money families sometimes looked down on new ideas such as indoor plumbing and fish knives, many held out for service a la Francais well until the end of the century. By the time Edward was king though, service a la Russe had become the standard in wealthy homes.

Over time, a la Russe came to mean a formal meal where everything is done simply and sequentially. The earlier way of guests either reaching for their food or helping each other was entirely eliminated. By the late Victorian period the fashion was for the service we recognize today, with savory dishes first, going from light to heavy, with breaks for sorbet and salad and followed dessert and then coffee. With this new fashion for individual courses served one at a time, came new dishes, glassware and silverware. Suddenly you needed a plethora of forks, knives and spoons to each each course to it’s best advantage. And differently shaped glasses to serve the wines that accompanied each course. The formal dinner became the one that we all recognize.

“Occasionally referred to as Russian or Continental, this style of service is an ambitious undertaking in the average home unless you have a maid or can call in outside help. When the guests enter the dining room, no food is on the table. A service plate is at each place. After the guests are seated, individual plates served from the kitchen are placed on the service plate before the guests. Or a servant may offer food from the left of the guest, who serves himself, or for the ultimate in formality, the food may be placed on each person’s plate. Serving is always from the left of the guest. The hostess is usually served first, then each guest in order around the table to her right. Occasionally, a highly honored guest is served first, then the hostess and so on around the table. The “ladies first” rule is repeated here, and guests are served in the order of their seating. When courses are changed, the hostess’ plate is removed first, then those around the table to her right in the same order as serving.”

Better Homes and Gardens, 1962

Something to note: As you see above, if you want to serve dinner truly in the Russian style, there should be no food at all on the table when guest are seated. The modern fad for having the first course plated and at the ready negates the perfect Service a la Russe. Now this may seem nit-picky, but Service a la Russe is the most formal service, so it is exactly these little details that matter.

If you hare hosting an Edwardian style dinner, note that the most formal form of service sees the guest serving themselves from a platter held by a servant. The act of the servant placing the food on the plate would have been gauche as that was how things were done in a hotel. Home service at that time was the standard for elegance. By the forties, American mindsets had shifted so far that the “hotel” style service was now considered the highest form of formality. I think this notes the shift from an English to American view of etiquette, with American’s viewing the skill of the server as being paramount over tradition. Or one could take the view that the English were interested in viewing the skill of their fellow guests in handling the serving implements, caring most about the class markers of their companions, where Americans were interested in the ability of the host to employ the finest servants with the most abilities and experience. But as will all things etiquette, this shift happened gradually and only in some places. The Brits continued to serve themselves well past the midcentury. Very old money in the US and Britain also held onto this form of service for much longer, some continuing to use it even today.

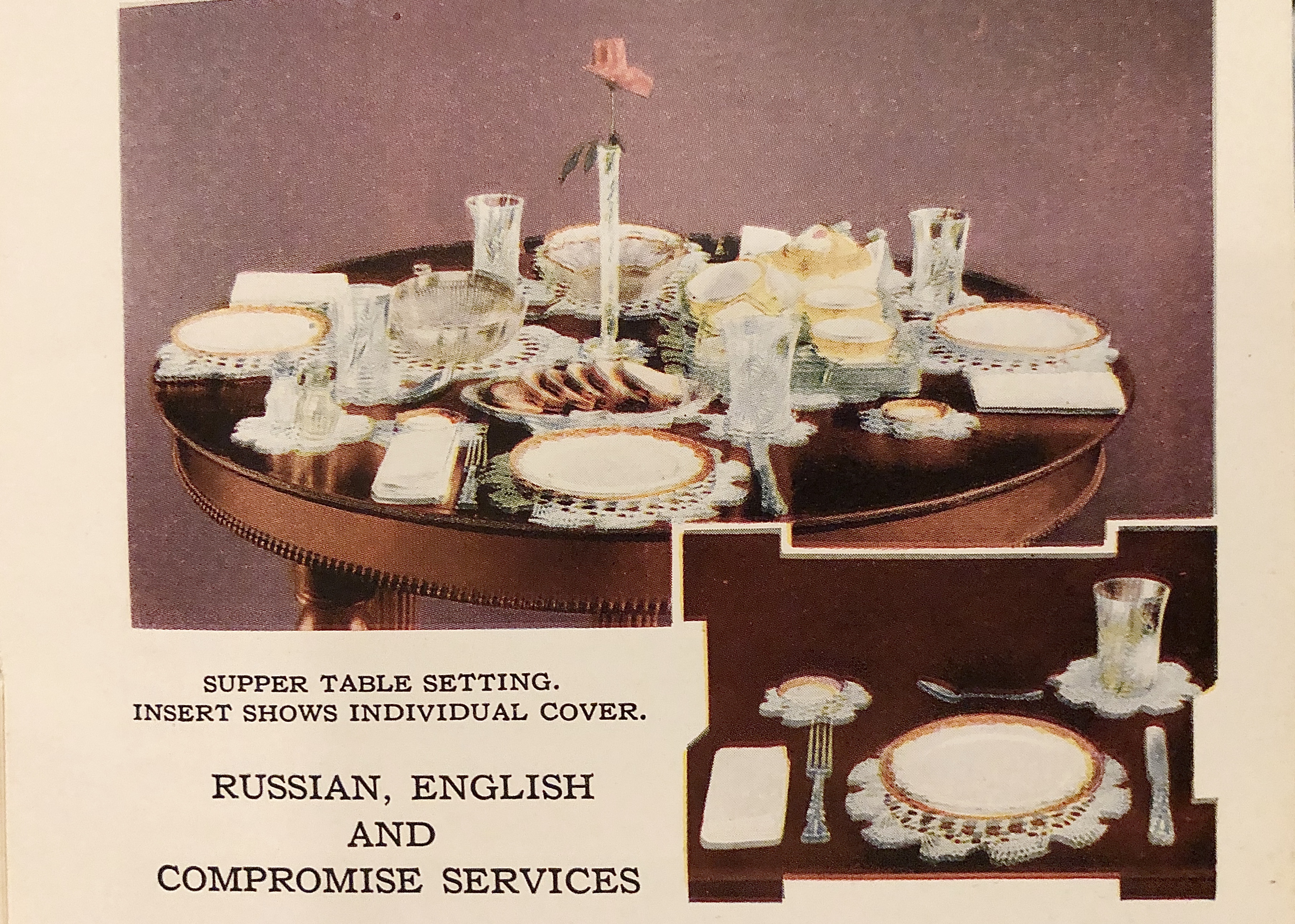

Compromise Service

This is a combination of French and Russian service, also know as the Anglo Russe Service.

It is exactly as it sounds a mix between the Russe and Francaise. There are several reasons for the compromise. One main reason was that most people did not have the number of servants to allow for every course to be served by footmen. The compromise service allows for many fewer wait staff. Ideally, in compromise service, each server would have no more than six guests. That means a couple could have four for dinner and only use a waitress or butler. The second reason is that many held to the tradition of carving that we talked about above.

In compromise service the first course is served a la Russe. An appetizer or soup is served by staff at the table, everything is plated in the kitchen and brought to the guest. The second course is meat and carved at the table. This allowed the host to show his skills and required no staff, as the host plated the meat and handed it down to the guest. The host might even put vegetables on the plate as well.

The last course is dealer’s choice. One could have staff bring dessert to table. The hostess could serve dessert at the table, though then the staff would remove the dishes and crumb the table, sometimes even removing the tablecloth to reveal a beautiful wood table. Or dessert could be served in an adjacent room with the hostess poring the coffee.

Remember that this is only for formal service. That means grand dinners. This does not mean banquets and it does not mean Informal or Family style dinners, which still might have had guests in attendance. And if you decide to hold a formal dinner, please, invite me!